- Lighthouse Foundation

- Issues

- The Course: Sustainability in practice

The Course: Sustainability in practice - The coastal community of Thorupstrand, Denmark

How to live a meaningful life without compromising the ability of others and future generations to experience the same

Thorupstrand is a small fishing village on the Danish North Sea coast. People have lived here for 1000s of years always adapting to the changing environment. Today, the basis of the community is fishing. Fishing has always offered perspectives for future generations here as long as the delicate relationship between exploitation and regeneration of the natural resources and human needs could be maintained. With the growing ability of humans to alter whole ecosystems - even far away from their home - this has become increasingly more difficult.

In the major port cities of the North Sea an industry of large-scale fishery is dominating. Their economies of scale rely on large vessel capacity and bottom trawling gear with high fuel consumption. They are mobile and can travel far distances for fishing. The fishers of Thorupstrand do not want to fish far away. They want to live and base their fishery where their families have lived for generations.

To understand how people in the region have managed to remain the last commercial landing place in the whole area, it is necessary to understand the elements and relations of the human and natural networks.

Introduction. Speaker: Thomas Højrup, Mathilde Autzen

Understanding the Ecosystem

The fishing village Thorupstrand is located on the north faced coastline of Jutland, Denmark, in the bay called Jammerbugten. The seabed of Skagerrak, the northern part of the North Sea, is characterized by chalk reefs, gravel, gutters and sandy areas near land. Further out there are several successive rock reefs between the sandbanks, old peat- and forest floor, soft holes, seaweed forests and limestone peaks with sandy bottom areas between.

>>> more information

Speaker: Mathilde Autzen

In the middle of Skagerrak, the slopes down towards the 600-800 meter deep gorge of the Norwegian Deep begins – a landscape formed by the ice ages. From here, cold, salty and nutrient-rich ocean currents flow in from the Atlantic Ocean and meet the North Sea water from the south, while freshwater flows from the Baltic Sea. This creates large primary production in the ecosystems of the underwater landscape and optimal living conditions e.g. for fish such as cod (torsk) and plaice (rødspætter), but also black lobster, crab, sole, octopus, catfish, monkfish, ling, turbot, grouse, halibut and all other Northeast Atlantic fish species.

During the summer, cod and plaice, target species for the local fishery, have the opportunity to move from the cold depths and into the warmer, richer sandy surfaces near the coast, and during the winter to move from the cold water at low depths near land and into the relatively warmer water in the depths – just as it suits them in relation to the changing temperature conditions of the seasons, the ocean currents, the supply of food items and their own reproductive needs. These conditions make it a highly diverse and species-rich marine ecosystem.

Skagerrak also holds a number of rare bubble reefs; biological reefs formed around cold seeps of geological carbohydrate outgassings, usually methane. These rare habitats are mostly known from the Danish waters of Skagerrak west of Hirtshals, but more might be discovered in future surveys. Bubbly reefs are very rare in Europe and supports a very varied ecosystem.

Ecosystem under pressure

All parts of the North Sea and Skagerrak are influenced by human activity, though to varying degrees. This is putting pressure on ecosystems and on animals and plants at all levels in the food web. Some of the changes that have been observed in conditions in the North Sea and Skagerrak can be linked directly to human activity. In other cases, the causal relationships are more complex and human activity is only one of the factors involved.

There is considerable concern about cumulative environmental effects on ecosystems in the North Sea and Skagerrak, particularly the impacts of hazardous substances, nutrients and eutrophication, bottom trawling and fisheries more generally, marine litter and underwater noise.

In the time ahead, climate change and ocean acidification are expected to intensify and have greater impacts, increasing ecosystem vulnerability. A higher sea temperature will result in changes in ecosystems. For example, warmer-water species such as sardines and anchovy are likely to become established, while other species disappear. Moreover, we know that CO2 emissions are making the seas more acidic. Ocean acidification may become one of the greatest threats to marine life both in these waters and elsewhere.

It is difficult to assess the scale of cumulative environmental effects because in most cases there is insufficient information on particular species and on the complex interactions in ecosystems. In addition, it is difficult to assess how vulnerable an ecosystem is to change.

The Fishing

The catching area of the Thorupstrand fishers is the southern part of the Skagerrak. They fish from the longshore bars along the shore to the rich slopes along the 800 meters deep Norwegian Deep. The fishery takes place within 20-25 nautical miles from the coast and the vessels (fishing boats) are mostly at sea for less than 24 hours. This means that the catch is landed daily.

>>> closer view on fishing

Plaice (Pleuronectes platessa) is the main target species from March to October and cod (Gadus morhua) from October to February. Depending on prices and the occurrence of migrating spawning Dover sole (Solea solea) there is also a small fishery for this species in March-May. Cod and sole are typically caught in gillnet whereas plaice is the main target species for the Danish seiners. Depending of the season some bycatch is taken and typical species are; Flounder (Platichthys flesus), dab (Limanda limanda) and more sporadic turbot (Psetta maxima) and brill (Scophthalmus rhombus) plus some codfish species such as hake (Merluccius merluccius), haddock 6 (Melanogrammus aeglifinus) and pollack (Pollachius pollachius). The European lobster (Homarus gammarus) and edible crab (Cancer pagurus) is taken sporadic in gillnets.

The Thorupstrand fishers way of fishing is eco-friendly because of the size of boats and the fishing techniques they employ. Two fishing methods are used: Bottom gillnet and Danish seine (Anchor seining). A short description of the two techniques is beneficial for appreciating the differences in environmental impact between these gear tyoes and large-scale fishery with bottom trawls.

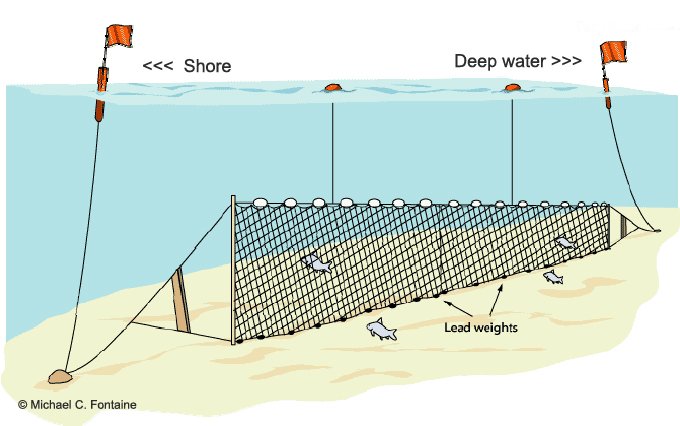

According to various studies, fishery with gillnet has a rather minimal influence on the sea floor (Jennings and Kaiser 1998, Rathje et al. 2011). A gillnet is a wall or curtain of netting that hangs in the water. A net is not towed over the bottom but placed static and with a minimal contact with the sea floor. There is, however, a risk of damaging corals if the gillnet is set on reefs. However, there is also the risk of damaging or losing the gear if it is set on reefs, this making this this unattractive for fishers. To avoid unintentional gillnet fishing in reef areas, the local knowledge, experience and skill of the fishers are of huge importance.

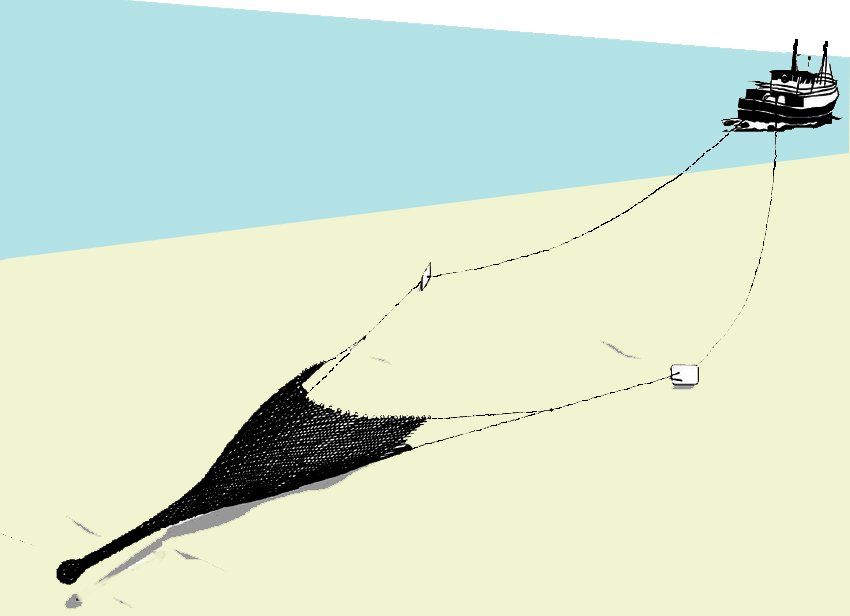

Danish seine (also called ‘anchor seine’) is a quite different technique. A seine is a small net formed as a bag placed at the end of a 3 km (local seines) long rope. The catch principle is as follows: At first the fishers sail in a circle while placing the ropes and the seine net in roughly a circular path at the sea floor. After the ropes have been placed at the sea floor, the vessel lies still at the anchor point and slowly draw the ropes back onto the boat. When the ropes are being hauled, that gear makes the ropes jump on the sea floor over and over again. This movement results in a continuously sound at the sea floor – like a knocking of a hammer. This audiovisual technique frightens the fish, and as the sound is getting closer and closer (as the ropes are been hauled in), fish swim towards the center of the gear. In the end, a big amount of fish is encircled in a small area in the middle of the gear and can easily be caught by the seine net just before being hauled onto the vessel. This means that the fish is still alive when landed.

The research on the impact of Danish seine on the sea floor is very scarce. The impact is understood to be restricted to the ropes being hauled over the sea floor. As this technique is only possible to carry out on sandy areas and as the gar is not towed after the boat, it characterized in Denmark as “low impact”. Further discussions on environmental effects of the different techniques can be found here: (Rathje et al. 2011).

As in all fishery discard is also an issue in Thorupstrand. Discard can be defined as all fish thrown overboard at sea after a fishing activity. These fish are caught unintentionally as a bycatch and must be discarded either because it is not in demand on the markets or because it cannot be landed due to quota restrictions or minimal length size.

In relation to environmental impact, consumption of fuel is another relevant subject. Across different studies based on literature values it seems a general conclusion – despite great variability – that both Danish seine and gillnets use less fuel per caught value of fish than bottom trawlers. Especially in Thorupstrand where the distance to the fishing spot is very short.

Data from literature on fuel consumption of gillnetters give values between 0,2 - 0,5 liter per kg caught fish depending on species compared to bottom trawlers with consumption values from 0,4 to 1,5 liter per kg caught fish. For Danish seiners the values vary between 0,12 l/kg/fish to 0,18 l/kg/fish depending on the target species. These values are again lower than the fuel consumption in the bottom trawl fishery.

When talking to the fishers in Thorupstrand it quickly becomes clear that the regenerative aspect of the fishery is vital to them. As most of them put it: Taking care of the sea is also taking care of their children and the next generation. The fishers themselves have made a code of conduct that describes how they interpret the interconnectedness of their livelihood and the coastal ecosystem. Among other things, it says:

“Our fishery is adapted to the natural behaviour and habitat of the fish, which change according to water temperature, current direction, waves, food and seasons. We only fish when the weather allows us to ensure that we can cross the breakers. When it is windy, the fish do not have to worry about us.”

For more information:

Rathje et al. 2011: A comparison of the coastal fishery from Thorupstrand to the conventional bottom trawl fishery with focus on environmental impact.

Jennings and Kaiser, 1998: Impacts of fishing gear on marine benthic habitats.

Kelleher, K. 2005: Discards in the world's marine fisheries. An update.

Understanding the community

In Thorupstrand there is no harbor. The vessels are hauled on to the shore at the so-called landing place after each fishing trip. This way of landing is the traditional way of fishing from the west coast of Jutland. The vessels used are all boats capable of being hauled on the beach. Most of them are wooden boats made of oak and a few are made from fiberglass. The boats need to be solid, but light in order to be hauled on shore – and this excludes large engines as a catch enhancing factor. Thus, a lot of the work on board is still done by man power.

>>> more information on the community

Speaker: Mathilde Autzen

The location of Thorupstrand is ideal for fishing not only because of the short distance to the rich fishing areas, but also because the village is sheltered from the strong western wind due to the north faced position on the costal line and the rock Bulbjerg west of the landing place. This makes it possible to haul the boats in and out also on days with relatively strong wind – deducing the number of days where fishery is not possible due to the weather.

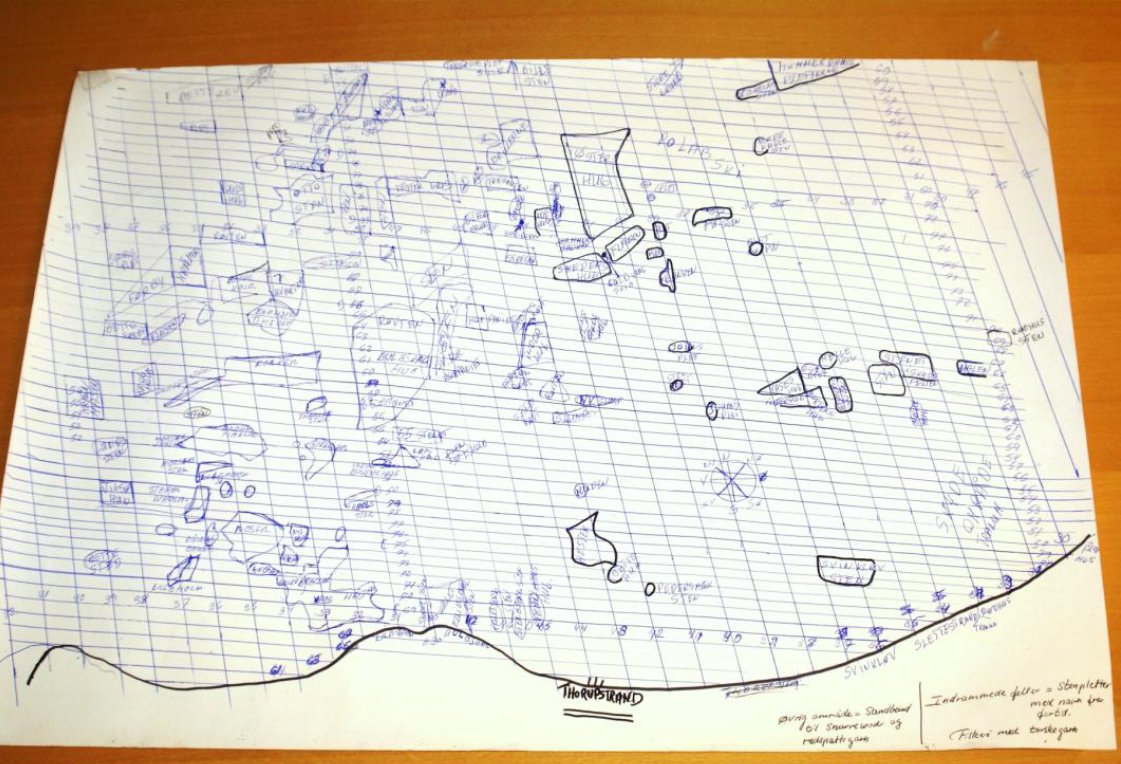

When tourists ask why they don’t build a harbor, many fishers answer: “Why should we?” The whole point of fishing here is the small-scale philosophy; keeping expenses to a minimum and relying on local fishing grounds. Living and fishing the same places their grandparents did – while experience, skill and knowledge is passed down from generation to generation. Handwritten maps reveal unique knowledge of the bottom structures: small reefs, areas with sand bottom, huge stones etc. Using these maps, the fishers have a privileged possibility to fish on the exact right spot depending on season and target species – guided by their grandparents’ skill and experience. Every stone and reef of the bay have a local history and are named accordingly.

The oldest of the remaining houses in Thorupstrand was built around 1715 when traders settled in the area. Until the middle of the 19th century trade (between Norway and Denmark) over Skagerrak was the center of the community, but slowly the fishery became the livelihood of the villagers. Fishery remains the main source of income in the village. While a few of the fishers of Thorupstrand fish from the port city Hanstholm, 30 km further west, the landing place at the beach continues to be the main workplace in the village. For every fising vessel roughly 4 people are employed on land: Gutting the fish, transporting the fish, selling the fish, maintaining and operating the landing place, maintaining and building the boats and fishing gears. Read more about how the wooden boats are built in the neighboring village Slettestrand.

In 2014 a new packing, sorting and icing facility was established in connection to the landing place, including a processing hall and a fish shop selling only low-impact caught fish. This modernization was possible due to donations from private and public funding seeing the value in promotion the eco-friendly fishery.

There is no grocery store in Thorupstrand so the villagers must go to Vester Thorup 4 kilometers further south for shopping. This village is mainly inhabited by farmers and the fishery leaves no trace of itself here except from the smokehouse selling fish. This reinforces the feeling of Thorupstrand being a very local and small community. The children of Thorupstrand goes to school in Klim, yet another small village further inland.

Speaker: Mathilde Autzen

The landing place is the center of Thorupstrand. This is not only a workplace but also the place villagers go to meet and talk daily. The main subjects are the fishing and the weather, but unlike a lot of other places it is not just something to talk about, but a very present and determination factor in the everyday life: can the fishers go fishing or not? The locals have a word for it: ‘Hawvejr’ (meaning ‘sea-weather’ in the local dialect). This underlines the fact, that the livelihood of the fishers is completely dependent on ‘nature’. Nature is not just something to ‘protect’ or ‘consume’, but an all times present factor to cooperate with.

When talking to the fishers in Thorupstrand, it is evident that fishing is not just a job, but a way of living as independent and self-employed fishing people. Being a wage-worker is a common joke to them. Fishing is not a means to profit, wage and leisure time, or a career. It is a way of living, and becomes an end in itself (Andresen, J., Højrup, T. 2008).

The permanent population in Thorupstrand estimates around 200 people. During the summer the population increase dramatically due to around 2.000 people visiting summer cabins in the area. And even more are visiting for only a day - leaving again in the night. This points to the fact that Thorupstrand is not just a fishing village anymore but also a growing tourist destination. People are coming to relax and enjoy the beach and forest, but also to watch the vessels being hauled onto the shore and catch a glimpse of the fishers ‘in action’.

Since 2015, four of the fishers in Thorupstrand have been the main characters of the national, weekly documentary called ‘Gutterne på Kutterne’ (‘the guys at the boats’). They have become famous for practicing traditional Danish fishing techniques and advocating better rights for small scale, ecofriendly fishery in Denmark.

In the local community there are conflicting feelings about the increasing tourism. On the one hand, many long to live as they have always done: As a local fishing community without tourism. On the other hand, there is an increasing awareness that they need the political attention and sympathy that tourists contribute to in order to ensure better fishing policies for small scale fishery. Questions have been raised whether it is possible to maintain the of existence of sustainable life-modes in the coastal communities, while tourism is introduced (read more about this: Højrup, T. 2011). Tourism is already creating a lot of jobs in the neighboring villages, and local initiatives such as a ‘Sustainability Festival’ is rising in the region.

Remaining as a small-scale local fishing community in an industrialized, global world is not an easy job. External forces such as privatized fishing rights and politics, EU legislations, and the stock market are both the foundation of existence and the biggest threats to the community. Being better armed to handle external forces the fishers in Thorupstrand to organized themselves as in a fishing rights owning corporative.

- Howdoes it do to people, if they exploit the sea and the natural resources they are dependent on instead of living with it?

- Is sustainable tourism possible? And is the sustainable co-existence of tourism and small-scale fishery a possibility?

Neo liberal capitalism and place based economies

The quota system:

In the early 2000s, the then-Danish government decided to introduce a new market-based management system for the country’s fisheries. Based on the concept of Individual Transferable Quota, it was a severe and far-reaching break with Danish fishing management traditions based on regulated equal and open access. In the new system the market replaced the state as the distributor of Danish fishing rights and the fishing quotas were tied to the existing fishing vessels, enabling boat owners to sell their allocated quotas for high market prices. As a result, investors, who had the eager backing of capital, started monopolizing fishing rights.

>>> read more

Speaker: Jens Ambsdorf

In the early 2000s, the then-Danish government decided to introduce a new market-based management system for the country’s fisheries. Based on the concept of Individual Transferable Quota, it was a severe and far-reaching break with Danish fishing management traditions based on regulated equal and open access. In the new system the market replaced the state as the distributor of Danish fishing rights and the fishing quotas were tied to the existing fishing vessels, enabling boat owners to sell their allocated quotas for high market prices. As a result, investors, who had the eager backing of capital, started monopolizing fishing rights.

The new system undermined the share-organized principles on which this type of fishing had been based and posed a serious challenge to the small-scale fishing communities in Denmark. New generations of fishers now had to buy into an expensive quota market or become borrowers of fishing rights from fishers who owned quotas. In another blow to the livelihood of the local people, fishers without boat ownership were not recognized when fishing quotas were allocated (read more: Autzen 2019).

Under the new management system, only about 1/3 of the Thorupstrand fishers, the boat owners, were allocated the valuable fishing quotas which created a vulnerable and uneven situation for the share-organised fishers, many of whom were the young generation who had not yet taken over from their fathers. Realizing that buying quota individually would be too big a financial burden, the fishers fervently looked for an alternative and decided to try and find a model that could secure present and future common fishing rights for their local community. The result was the formation of the “Thorupstrand Guild of Coastal Fishers”, conceived and designed as a “cooperative”. Their first act was to persuade local banks to lend them money to buy up fishing quotas for their guild. These common quotas are shared by the fishers and distributed yearly through a flexible distribution system. Anyone who is a registered fisher can become a member of the guild, as long as s/he signs the guild’s code of conduct for responsible and low-impact fishing, and promises to be based in Thorupstrand.

To become a member of the guild, one has to pay a deposit of about $15,220 US (100,000 DKK) that is refunded when one leaves the guild, but the values of the guild, the fishing quotas, stay in the guild for future fishers and can never be made object of speculation. In the guild, everyone has an equal right to their shared quotas – meaning that share-organized fishers without boat ownership are equal and valuable partners for boat owners. In order to repay their bank loans, the fishers in the guild pay a rent for the common quotas they use, and as such their loans are lowered until that day in the future where the guild is debt-free.

Most of the founders of the guild are now retired, and their memberships have been taken over by younger fishers. The guild has thus been able to achieve one of its primary aims, to provide access to fishing rights for the young generation. (Autzen 2019)

Today it is a worldwide well known fact that a legal forced privatization of fishing rights paves the way for a smooth concentration and monopolization of quotas in the hands of a few investors whereas most coastal communities and fishing people are stripped of access to their resources. The Thorupstrand example shows that on the basis of the share-organised system and its culture, it is possible to build a common pool of quota rights ensuring the community a share in the resource and providing fishers with an interest in conserving this resource for future generations – legally and biologically. But this experiment also revealed that the necessity of securing loans in order to pay large sums for quota weighed down the community company with a vast debt, making it vulnerable to external factors such as banking changes under the financial crisis, gambling investors, and falling prices of fish in Europe

Industrial and place based economies

Another driving forces for the destruction of local fishing economies are long distance industrial trawlers. Shipping companies in European ports have financed fleets of large vessels to fish at well-known fishing grounds, concentrating their effort in areas with a high prevailance of fish in certain seasons and benefiting from industrial advantages of scale. In this type of fishery, the size of the catch is the determining factor of competitiveness, and large vessels can compete by storing and transporting fish over great distances. In six centuries this fishery has supplied Europe with dried, salted, canned and now frozen fish from distant oceans and fishing banks. The other mode of production is a multi-species near-shore fishery, practiced by selfemployed fishers in many small coastal communities all around Europe. This simple commodity mode of production has a long history, and still occupies around 80 % of the fishing people in Europe. They fish together in tight and flexible crews, sharing the earnings in such a way that the boat and gear owners and each crew member get a share. This share system means everyone on board any given boat is motivated in operating the fishery efficiently and sustainably. This mode of fishing delivers fresh fish, caught on the same day, to market, and has for centuries supplied the coastal regions of Europe with fish. Share fishing in European coastal communities can be described by the distribution principle of joint income for a Danish sea boat with three crew members as given in the example below: Variable costs such as the winch or harbour, diesel oil, cleaning, packing, and the auctioneer’s fee are paid in advance. The remaining joint income is paid out as follows:

- 20 % vessel (for maintenance and repair)

- 20 % nets, lines, snares, etc. (for maintenance and repair)

- 20 % skipper (share fisher, and most likely owner of a share of the vessel)

- 20 % second crew member (share fisher, and eventually owner of a share of the vessel)

- 20 % third crew member (share fisher, most likely a young man)

As a partnership, in the event that the value of the catch does not exceed the variable costs, the partners are financially obligated to take the loss and earn, in effect, a negative income.

>>> more information

Currently, the fishing community is challenged by low levels of catches of their most important target species. They face hard competition from foreign beam-trawlers that take over their fishing grounds and, according to the small-scale fishers in Thorupstrand, destroy the sea floor, putting the future resource base in danger (read more: Autzen 2019)

Since 2007 the fishers of the guild have taken several measures in order to address these challenges. Among other things they have upgraded their common facilities in order to secure the best quality fish for the auction. The guild has opened its own local fish shop, and also initiated a partnership with a Danish retail chain. A recent interesting step was the opening of a floating fish shop in Copenhagen (Illustration 5: Floating fish shop in Copenhagen). The guild has also started a collaboration with marine biologists to continue to be technically and scientifically sound in their work. At the moment the guild is trying its hardest to protect the local fishing grounds from heavy beam-trawling and make sure that the local ecosystems will remain sustainable for future generations of local small-scale fishers (Autzen 2019).

The environmental impact of marine fishing is subject to growing public and political awareness. The effects of bottom trawling have long been known – effects like the physical disturbance and flattening of the sea floor, the resuspension of sediments and the destruction of non-target benthic animals, especially non-mobile forms like corals and sponges (see reviews by Jones, 1992; Dayton et al., 1995; Jennings and Kaiser, 1998; Clark and Koslow, 2007). (Rathje et al. 2011:13). Rewriting is needed

Over-fishing in Europe:

The report’s evaluation of the EU and its member states’ policies over the last decades constitutes a harsh self-criticism. The Commission emphasises that the main problem is over-fishing in European waters, which they consider to have been caused by overcapacity in European fishing fleets. (http://havbaade.dk/european-fisheries-at-a-tipping-point.pdf

)

Visions of making Han Herred into a Nationalpark:

The area around Thorup Strand has been pointed out as an ideal places to make a new national park: https://danarige.dk/naturnationalpark-hanherred/

Transferable Fishing Concessions - The solution to overfishing or a problem in itself?http://www.havbaade.dk/Fish-for-the-future.pdf

long distance fisheries

The first of these is mobile long distance fisheries. In these, shipping companies in European ports financed fleets of large vessels to fish at well-known fishing grounds, concentrating their effort in areas with a high prevelance of fish in certain seasons and benefiting from industrial advantages of scale. In this type of fishery, the size of the catch is the determining factor of competitiveness, and large vessels can compete by storing and transporting fish over great distances. In six centuries this fishery has supplied Europe with dried, salted, canned and now frozen fish from distant oceans and fishing banks. The other mode of production is a multi-species near-shore fishery, practiced by selfemployed fishers in many small coastal communities all around Europe. This simple commodity mode of production has a long history, and still occupies around 80 % of the fishing people in Europe. They fish together in tight and flexible crews, sharing the earnings in such a way that the boat and gear owners and each crew member get a share. This share system means everyone on board any given boat is motivated in operating the fishery efficiently and sustainably. This mode of fishing delivers fresh fish, caught on the same day, to market, and has for centuries supplied the coastal regions of Europe with fish. Share fishing in European coastal communities can be described by the distribution principle of joint income for a Danish sea boat with three crew members as given in the example below: Variable costs such as the winch or harbour, diesel oil, cleaning, packing, and the auctioneer’s fee are paid in advance. The remaining joint income is paid out as follows:

- 20 % vessel (for maintenance and repair)

- 20 % nets, lines, snares, etc. (for maintenance and repair)

- 20 % skipper (share fisher, and most likely owner of a share of the vessel)

- 20 % second crew member (share fisher, and eventually owner of a share of the vessel)

- 20 % third crew member (share fisher, most likely a young man)

As a partnership, in the event that the value of the catch does not exceed the variable costs, the partners are financially obligated to take the loss and earn, in effect, a negative income.

Leave your thoughts for further discussion

- What is sustainable in this community, what is not?

- What is your idea for the future?

- What needs to be done?

- Can you contribute anything yourself?

- Do you know similar situations?

- ...